As I type these words, my month long artist residency with New Harmony Clay Projects is coming to an end. I am sitting in the corner house situated between a Roofless Church and a Grapevine Bar. The church is as roofless as it sounds and the bar lives up to its name with its charming vaulted ceiling covered in painted grapevines.

I’ve been living in this corner house, one of the original Harmonist log cabins built in the early 1800s, known as the Barrett-Gate House, with two other artists in residence: Sarah Alsaied and Grant Akiyama. Together we live amongst the many ghost stories that permeate old historic buildings secluded in sleepy ghost towns.

This one in particular is located in New Harmony, Indiana.

Between the creaking floors and flickering lights and from behind the door that unlatches itself, I finished reading Jenny Boully’s Betwixt and Between: Essays on the Writing Life, concluding with the essay “On Beginnings and Endings.”

“An ending tumbles toward you over and over again; an ending will not stay flat, will not stay put; an ending troubles and taunts; an ending is sleep lost.

An ending is a puzzle without a picture; an ending says that despite whatever it is that one of us wanted, nothing more can be done.”

“A beginning is asking: more please.”

On my first walk around town, it didn’t take long to notice a theme of labyrinths. Graphically they appeared in various scales. Some stretched above my head, painted white on red brick, while others greeted me in small details— painted blue and white on the town hall sign.

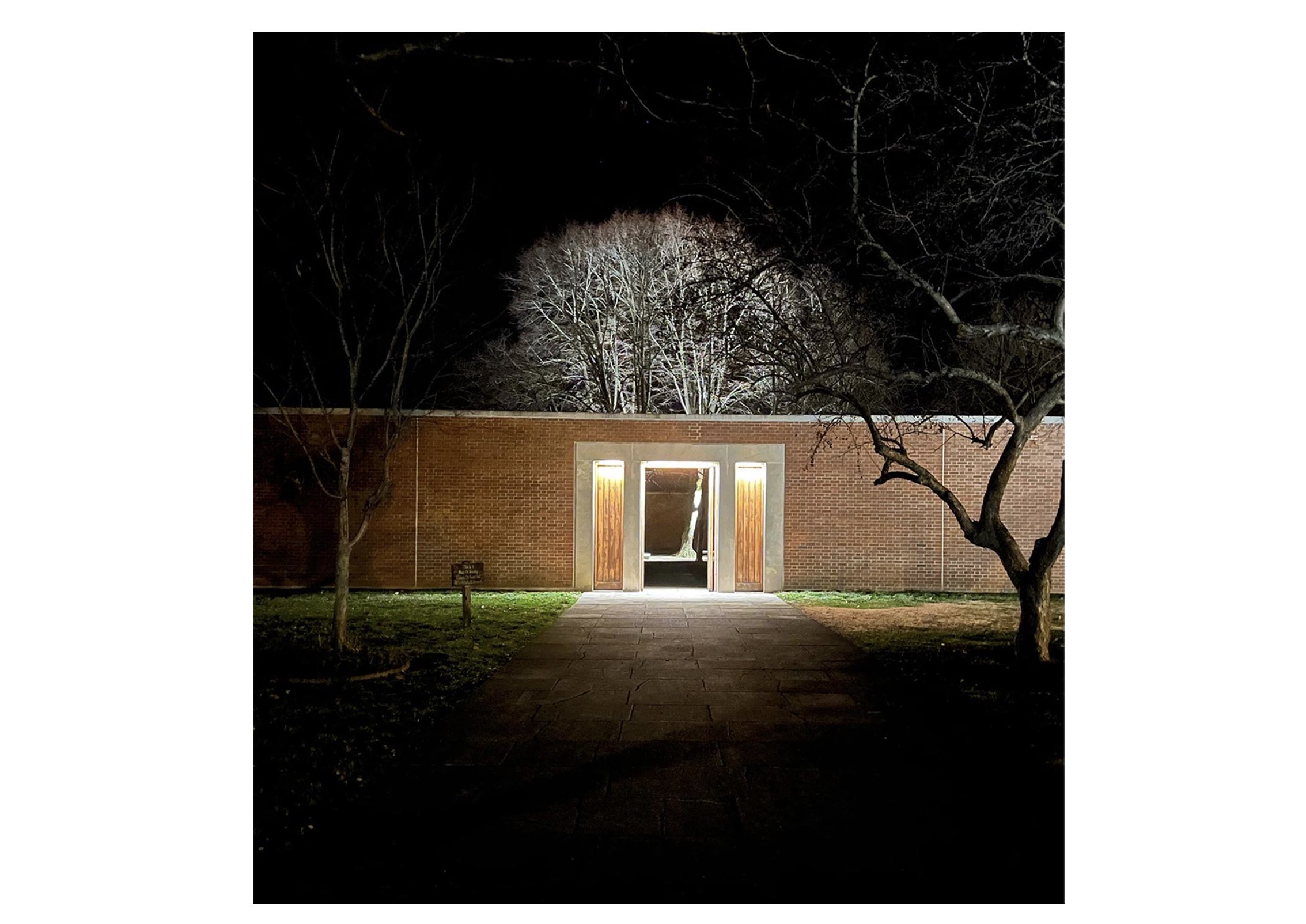

Adjacent to the studio, I found an interactive walking labyrinth. Officially it is called the Cathedral Labyrinth and Sacred Garden. Its path is burnt onto the surface of polished granite, following a geometry based off of the French Chartres Cathedral, considered the “mother labyrinth.”

In New Harmony labyrinths are embedded in the history of this town. In 1814 it was the site of a religiously oriented Harmonie Society inspired by ideals of a utopia and the work of German theologian Johaan Valentin Andreae who designed a utopian labyrinthine city called Christianapolis.

On my orientation tour facilitated by New Harmony Clay Project’s Program Manager Mitzi Davis, it was noted that a labyrinth is different from a maze.

According to Hermann Kern’s in depth research that traces the histories of labyrinths from the Bronze Age to the present in his book, Through the Labyrinth: Designs and Meanings, the reason that mazes and labyrinths have become obfuscated over time is due to the way they have been employed as literary motifs.

I stumbled upon this thick compilation of research at the Working Men’s Institute first floor library. The second floor houses the museum and art gallery. Davis aptly described the museum as a wunderkammer or cabinet of curiosities; recommending it to see the taxidermied eight legged Siamese twin calf from the 1800s.

It is a thing of nightmares with true New American Horror Story potential. Which I suppose is fitting for a town that Joni Mayhan, local paranormal investigator and author of Haunted New Harmony describes as:

“a thin place — a place where the veil between the living and the dead is especially transparent, like a sheet left on the line too long.”

While Mayhan writes about how the entire town is haunted with each chapter touring you from one haunted building to another; spiritual places such as labyrinths are the only exception.

The Roofless Church being another.

Kern pinpoints that as a metaphor the labyrinth signifies a difficult, unclear, confusing situation. He notes that its proverbial usage links the labyrinth to the concept of a maze as a tortuous structure, appearing with many paths, dead ends or blind alleys. However, Kern emphasizes that depictions of labyrinths (graphic or physical constructions) from antiquity to the Middle Ages, and up to the Renaissance only demonstrate one path with no possibility of going astray.

“The most important part of a labyrinth is the negative space of the path formed by those lines which determine the pattern of movement - the shape of circuits inside.”

“As a graphic, linear figure, a labyrinth is best defined first in terms of form. Lines appear as delineating walls and the space between them as a path…the sole function is to define choreographically a fixed pattern of movement…a walking path between the lines.”

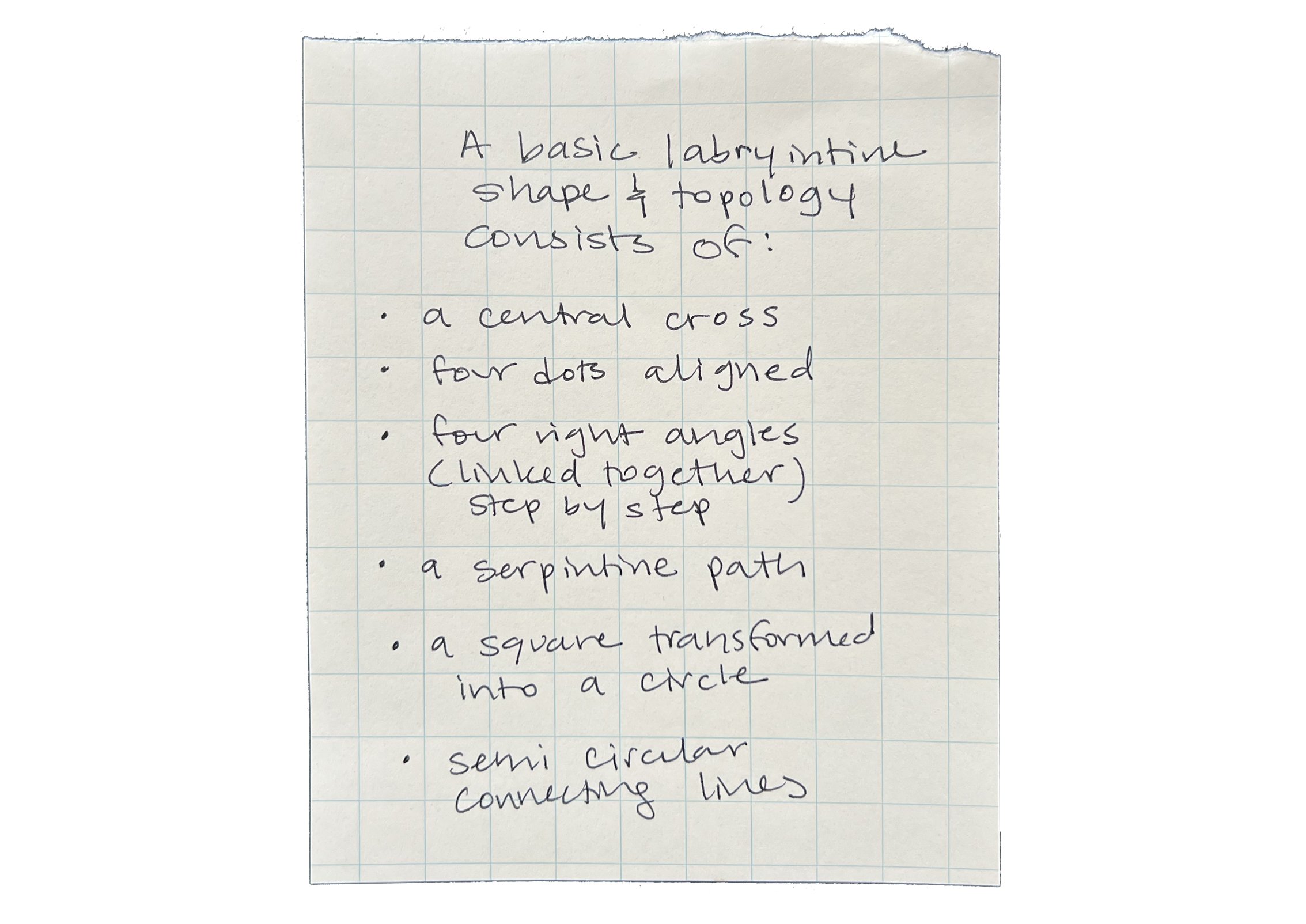

How to construct a labyrinth

Just as a labyrinth is not a maze, Kern also stresses that they are not spirals, meanders, knots or concentric circles either. A meander doesn’t have a center. A knot or woven pattern are many lines intersecting or single lines that circumscribe themselves. A spiral is not completely enclosed by an outer line or continual, pendular changes in direction. And concentric circles can only be a labyrinth if each circle has an opening that can be entered.

While the layout of the path is not fixed and has many varying designs throughout history and cultures there are principles of form.

The transformation of a square into a circle or the phenomenon of squaring a circle reveals, according to Kern, how both shapes: squares and circles can simultaneously orient locations and symbolic meanings. A square mimics four points of a compass and a circle reflects the circumference of surface area.

Both shapes are inherent to a labyrinth and represent a worldview of the circle as a symbol of the heavens and the square as a symbol of the earth. The sign posted outside of the Cathedral Labyrinth shared that Native Americans consider the circle sacred, referring to the circle as “the hoop of life” — the continuity of life and eternity.

Circles keep reappearing. Before arriving in New Harmony, I listened to Lisa Congdon’s podcast: Episode 30: A Conversation with Morgan Harper Nichols on Wholeness. Throughout the episode she discusses her definitions of wholeness deriving from a Rilke poem:

“I live my life in widening circles that reach out”

For Harper Nichols, wholeness is a circle— many circles. “Wholeness is drawing from the present in unlikely places with unlikely connections.”

I found this to be true while walking by the Wabash River behind the Antheneum Vistor’s Center and stumbling upon Eames Demetrius’ site specific markers: “written stories (often in bronze, concrete or stone) that emphasize not only what is written but where you experience the reading (and often the forms).”

These markers are part of his ongoing series titled Kcymaerxthaere - the name of an alternate universe that he claims to coexists with ours.

The title derives from two cognate words (words in two languages that share a similar spelling, meaning, and pronunciation):

kcymaara: true physicality of the planet

xthaere: a shape with almost an infinity of dimensions or sides

Demetrius, who refers to himself as a “geographer at large,” describes this series as a storytelling experience, “reading as a fulcrum into or with another world…stories as renavigation.”

“ A sentence is an archipelago of words.”

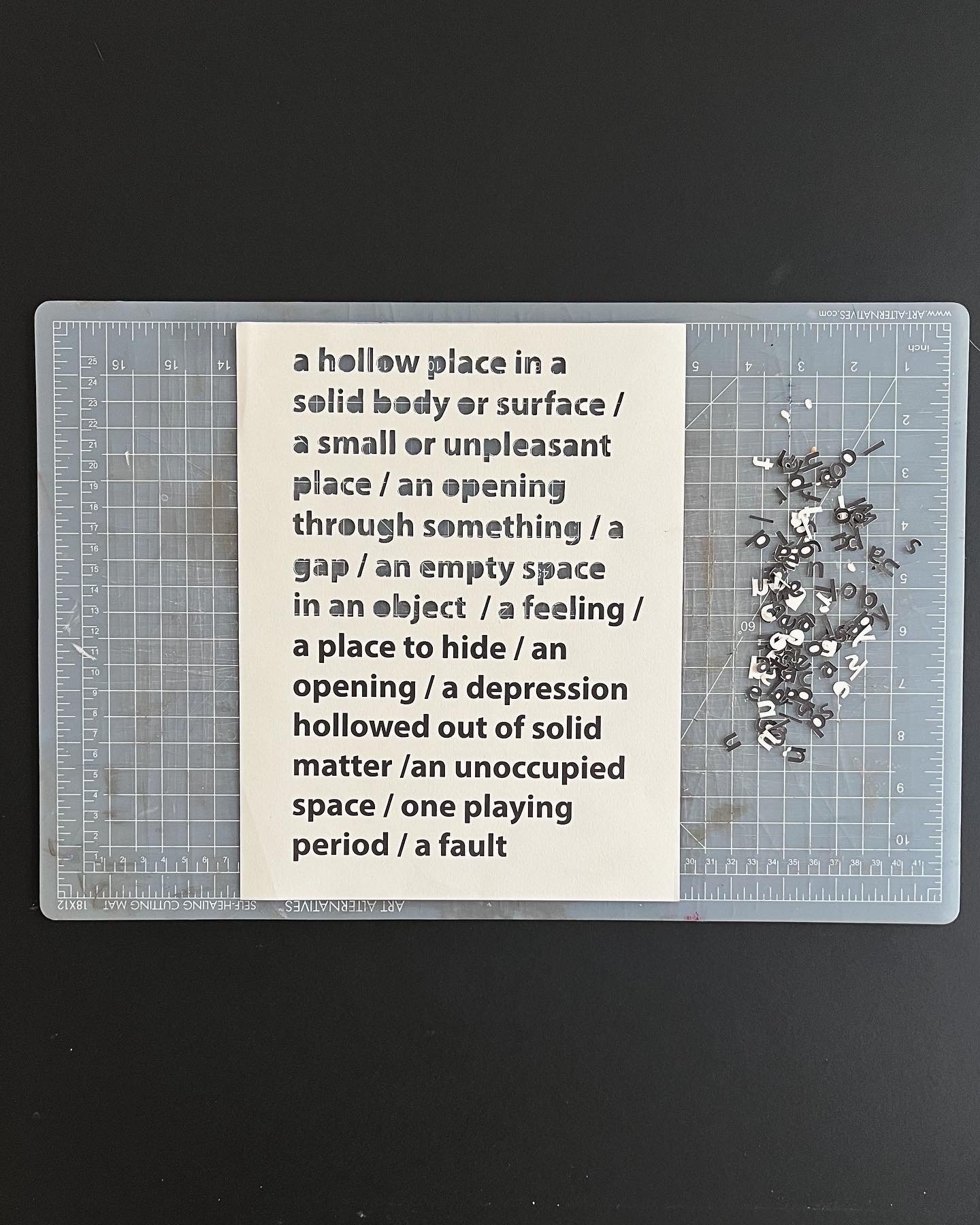

I came to New Harmony Clay Projects as an artist in residence to research and experiment with creating a series of vessels designed with holes using methods of additive and subtractive clay construction to mimick the homonyms: whole and hole.

In preparation for my residency, I purchased Hilary Plum’s latest book, Hole Studies. I was intrigued by Plum’s definition of a hole as how to care for a question. Although she doesn’t directly say this. Plum writes of holes on various topics that encompass the personal and the political. She writes about holes as boring, unsupervised, slow paced office jobs with sentences that say “when your husband is dying you get a job that pays better.”

A hole is an email that begins with sorry i’ve been slow to write back.

Many of her studies of holes exists as but are not limited to: tunnels and research on jobs in academia and writing and for caregivers or those caring for the caregivers. She reflects on her role and experience as a teacher. In teaching, a hole becomes “a space for a circle…a threshold between knowing and unknowing, attuned to surprise…a willingness to adapt and shift..and how to care for a question.”

At the heart of my inquiry of the homonyms whole and hole is a question that I keep coming back to — when is absence present or presence absent?

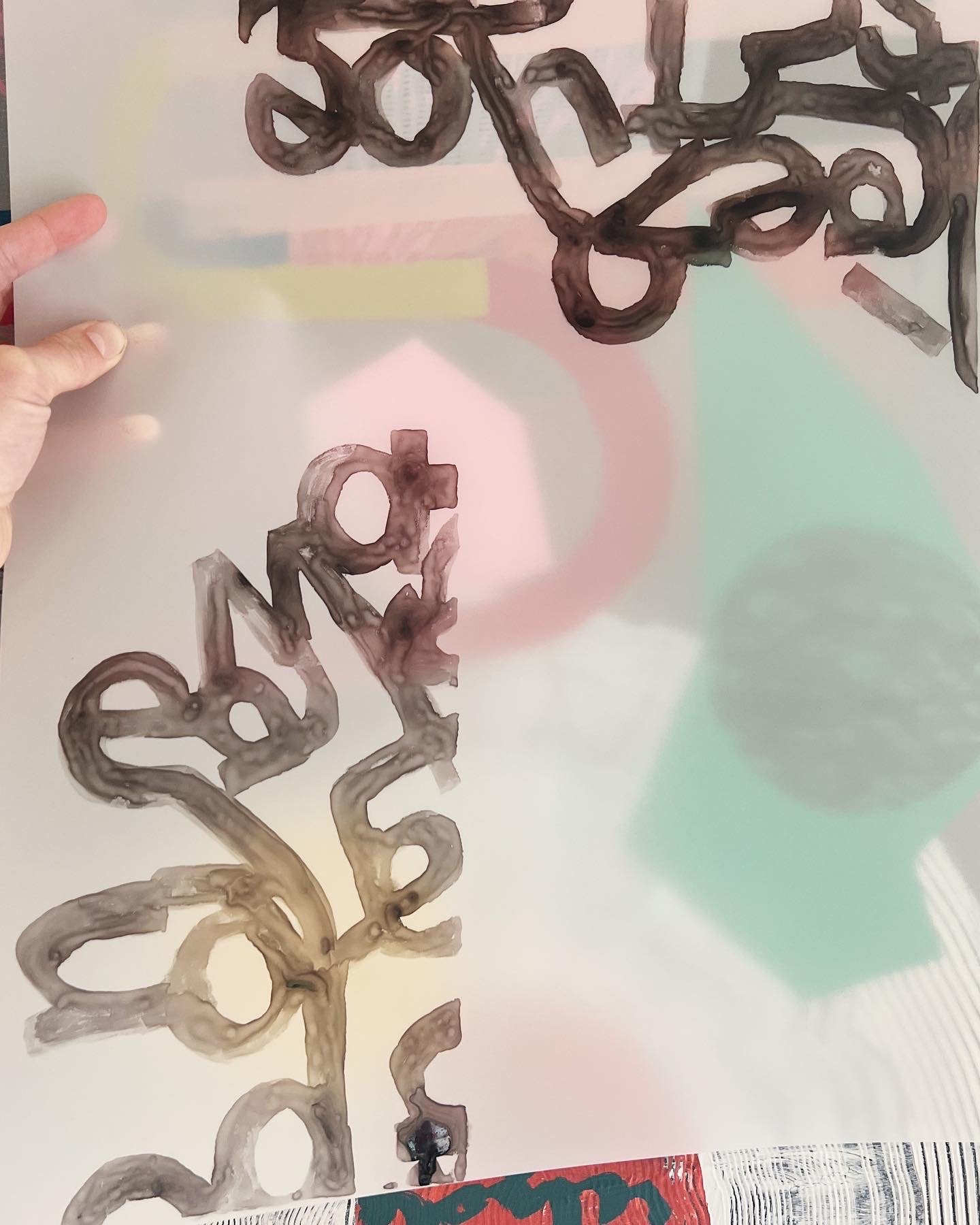

While ruminating on this question, I began to compile sets of definitions and proceed to cut them out by hand, either subtracting the words letter by letter or the space around the words. The leftover remnants, the in-between shapes or lone letters broken from their words, became material for new compositions.

Burrowing further, pieces began to connect in the process of arranging, assembling, gluing, scanning, printing, tracing, painting, transferring, burning, screen printing and then repeatedly painting, cutting and pasting for a second time.

Holes are subtractions that reveal what is missing, acting as a threshold between interior glimpses and exterior facades. Added objects prod and poke, nestle in crevices and corners, turning holes into containers. These elements fill in gaps, mend what was broken or meet you in the center.

Words can be vessels—deep wells to fall into and shallow entrapments.

An erasure practice is both additive and subtractive simultaneously. Poet and scholar Robin Coste Lewis lectures on the many forms of an erasure practice. Language itself being one. Lewis articulates that erasure is the art of creating a new work out of an existing one. What the poet Jeannie Vanasco calls “absent things as if they are present.”

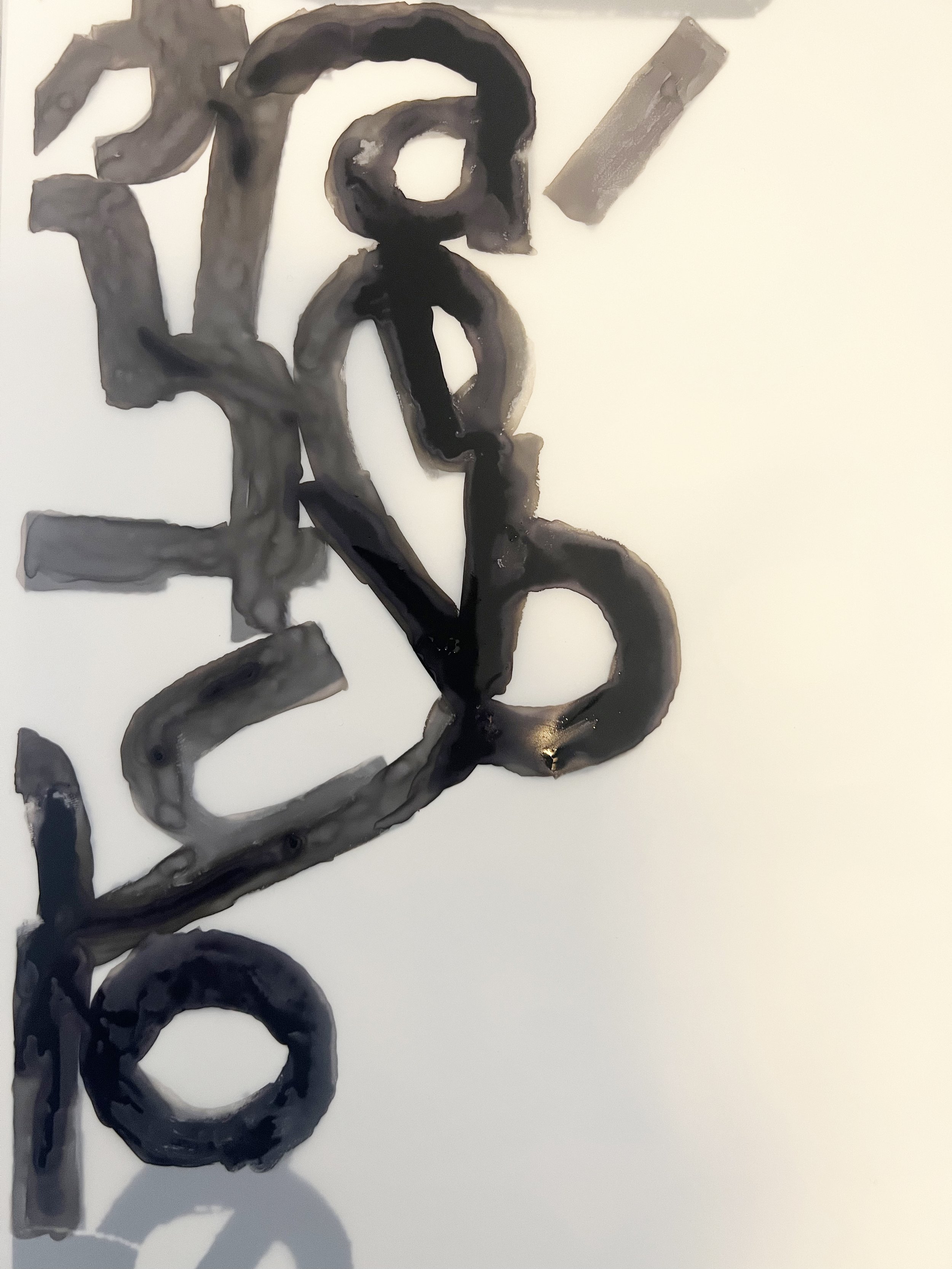

These abstracted ceramic letter forms are erasures. Initially found as fragments on the ground, I reproduced them with clay pressed into a plaster mold. Rather than translating a word or phrase, I was more interested in their materiality. By allowing the letters to touch they become something new, a (w)hole, a meandering path, lost in thought and lingering in cast shadows and the ghosts of stories they once knew.

A week into my residency, I finished a notebook I had started a year prior. Curious, I decided to collect the found fragments from my own writing to see what they might say.

While cutting and cropping my words, erasing and pasting their fragments back together, I decided to see what happens when I take them off the page and allow them to sit upright.

I am very grateful for this time to experiment and ask questions of ceramics. Thank you to Lenny Dowhie, Mitzi Davis, Elizabeth Garland, and the welcoming community of New Harmony as well as financial support from The Regional Arts & Culture Council’s Arts3C Grant for this opportunity.

And to Mo, the studio cat