For a second consecutive year, I have had the opportunity to attend a workshop hosted by Pacific Northwest College of Art’s Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing Program. Alejandro de Acosta led a three day Translation Class asking participants to read, write and experiment like a translator; inviting all monolingual, bilingual and multilingual learners to participate.

Which one are you? (quote from Lily Meyer)

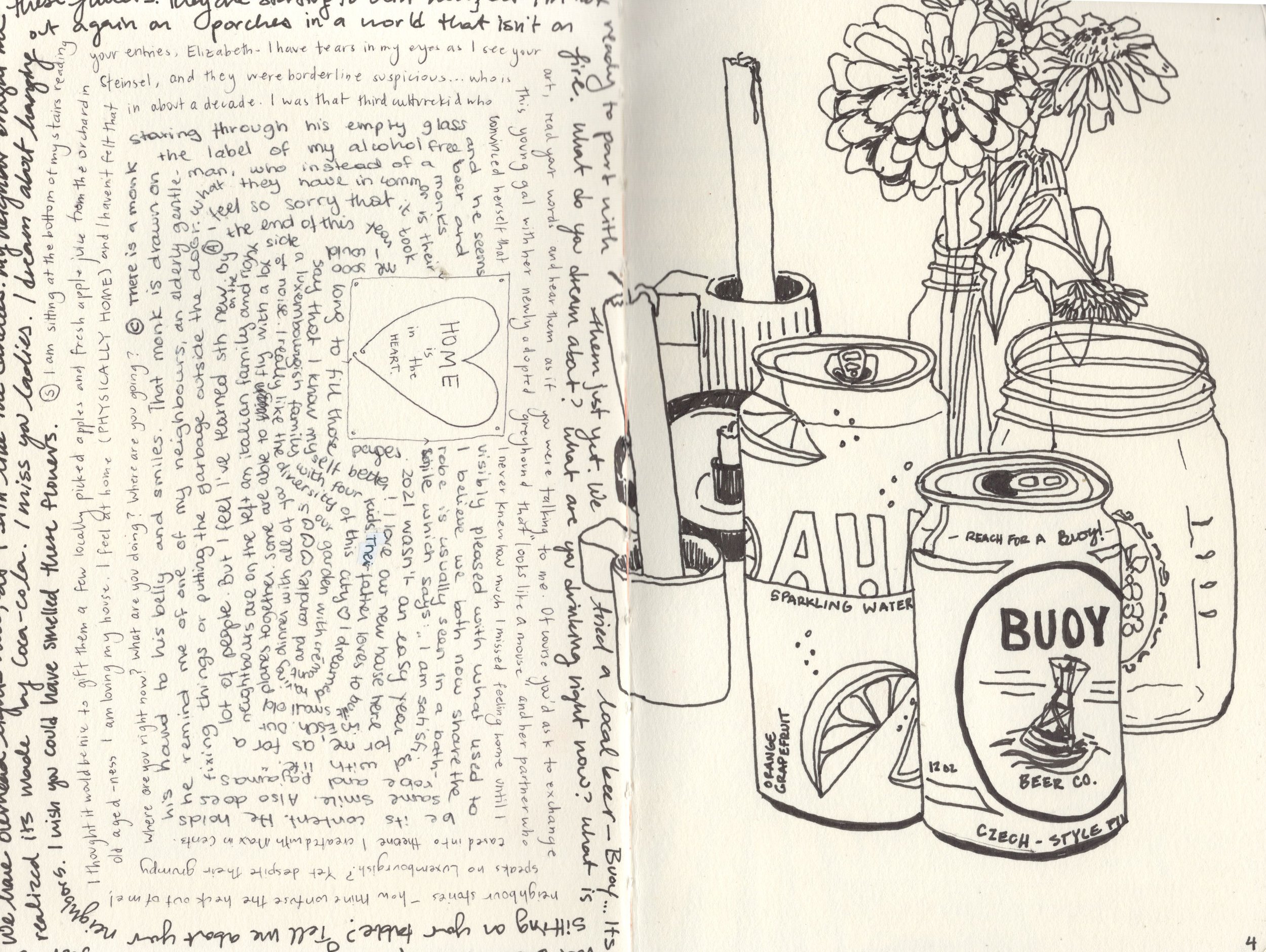

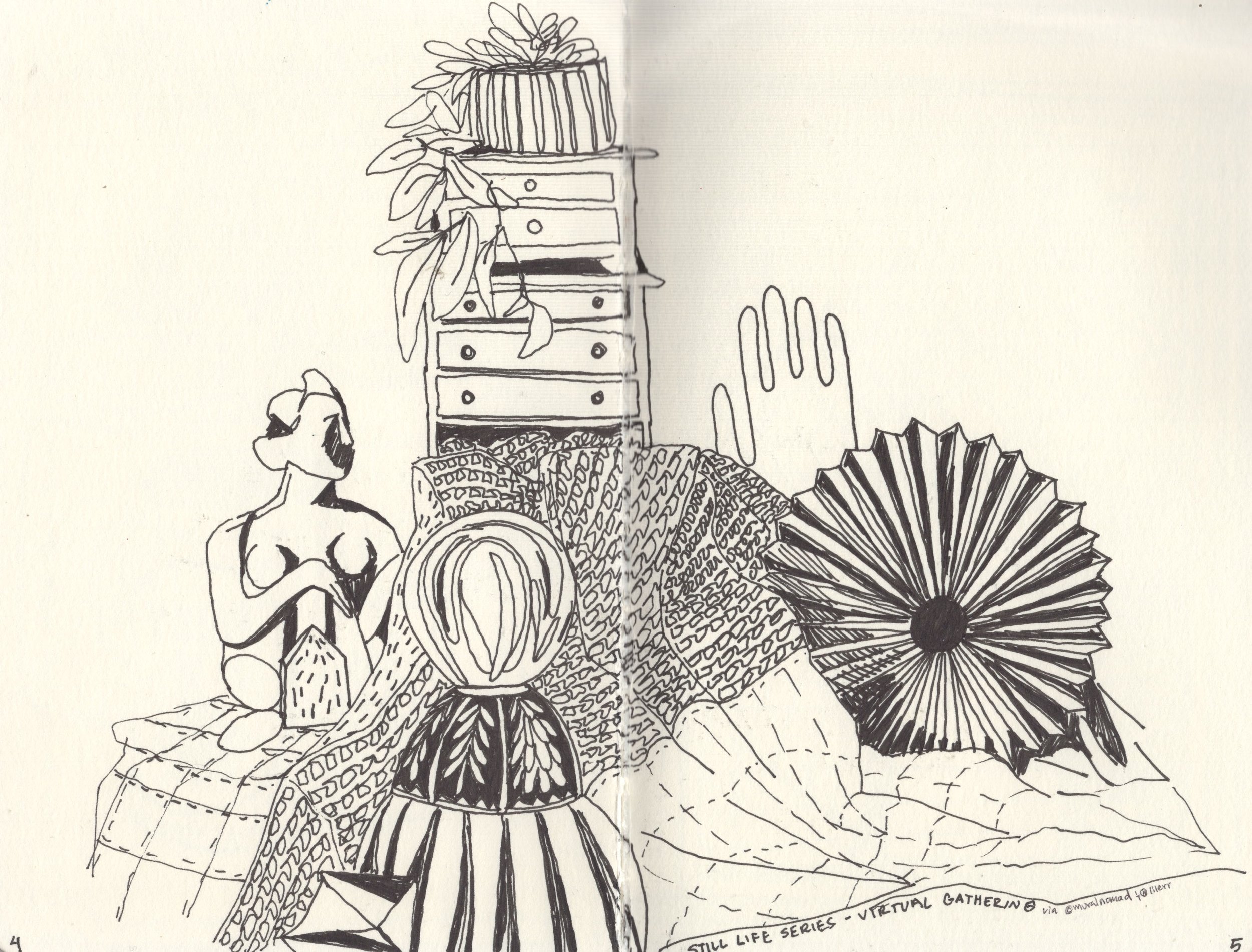

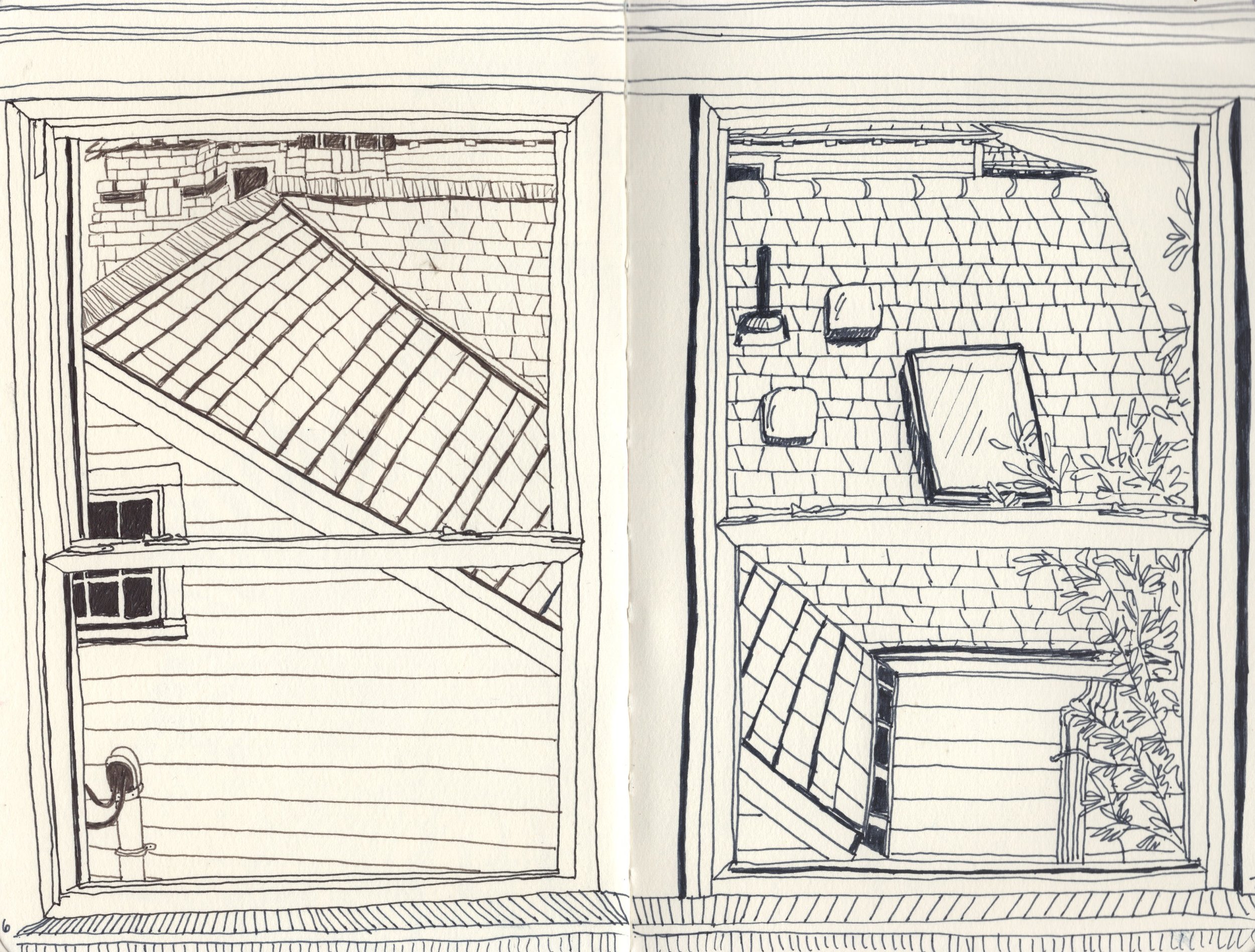

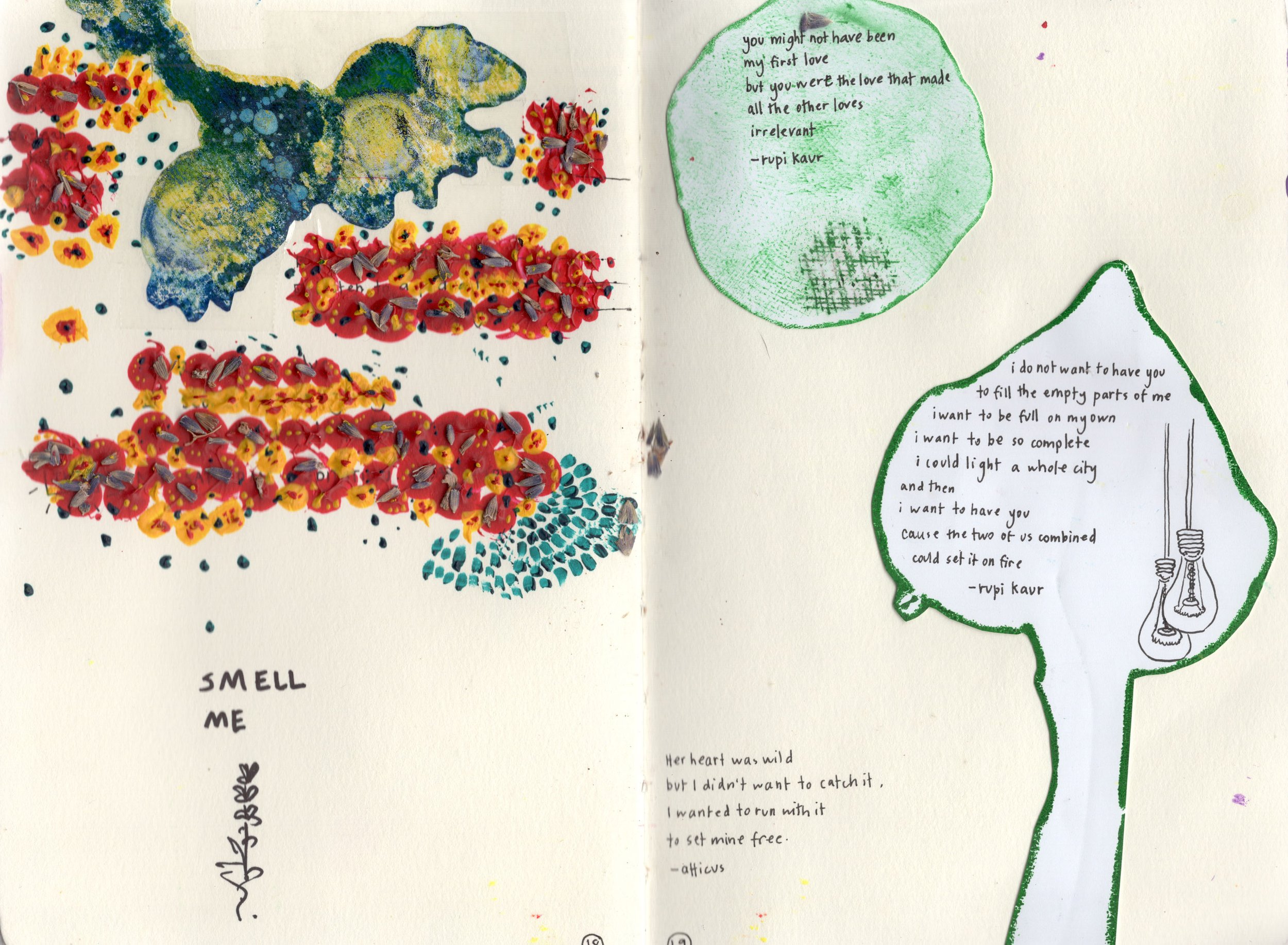

As a maker of things, my relationship with the concept of translation has predominately been focused on capturing or replicating the essence of something (i.e. an experience, a form or tone, a mood, a perspective, etc.) in different media. Translations between image and words (including those that were never there to begin with).

Translation as connection: lines assembled by their color and texture. Sometimes they are continuous lines of clutter - an attempt to translate grief from a fine tipped leaky pen.

Things I heard Alejandro de Acosta say about translation

For this workshop the lines were a vast and varied reading list. Many of the articles were a dense discussion of famous writers’ styles and varied perspectives on the art of translation. Vladimir Nabokov, Jorge Luis Borges, Ezra Pound, Augusto de Campos and Macedonio Fernández are prominent in these selections. It also covered the Oulipo group (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle) with their writing constraints, citing Georges Perec’s famous French novel, La Disparition (1969) written entirely without the letter e, later translated to English adhering to the same rules by Gilbert Adair in 1995 under the title, A Void.

I’m new to Perec’s writing and currently in the midst of reading his book, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, which I decided to use for de Acosta’s first assignment.

Step One: Translation as Research.

By intentionally focusing on the translator’s notes, in this case provided by, John Sturrock, I began to read his introduction and footnotes as a set of index cards, a trail of histories, tracing down clues, and recovering hidden backstories. For Sturrock translation acted as a type of collaboration. As a reader, the experience made me feel like I was being let in on newly found secrets.

Excerpt from Sturrock’s Introduction to Georges Perec’s Species of Spaces and Other Pieces.

Step Two: Stage a Return.

I followed Sturrock’s footnote on page 33 that explained the source of Dame Tartine’s Palace in Perec’s line:

“…it could be a sort of Dame Tartine’s Palace,* gingerbread walls, furniture made from plasticine, etc.”

In my staged return I discovered the nursery rhyme which details a beautiful palace made of fresh butter with praline walls and biscotti floors; illustrating the specific interior design of Dame Tartine’s French gingerbread house, which I would not have pictured otherwise.

By day two de Acosta was arguing against definitive translations, preferring a more open door method; translation as ongoing. In the section of the workshop titled: Pound & The Cribs, de Acosta shared ways in which American Poet Ezra Pound approached translating Chinese poetry without knowing Chinese.

Pound relied heavily on the help of scholars, dictionaries, notes and the word for word “cribs,” written by Ernest Fenollosa in order to write and publish Cathay, his famous book of translated Chinese poetry in English.

Example of Cribs used by Ezra Pound

de Acosta encouraged experimenting with translation in this way. Calling a text with facing pages, a two page spread of something already translated, as a modern day crib. I selected Francis Ponge’s poem, Pluie, translated by C.K. Williams.

Excerpt from Francis Ponge Selected Poems pg 6-7 (I would have liked to have shown you the entire page of “cribs” but Wake Forest University Press would need to give me permission)

My translation is as follows:

This exercise in translation gave me a new understanding of what de Acosta meant when he said “translation is a painful thing, always imperfect - a source of joy.”

I still prefer translating in visual media over translating between words.

Like the way I can translate a bottle from glass to ceramic with the use of a two-part plaster mold as my Google translator, a similarly inconsistent mystery box with varying results.

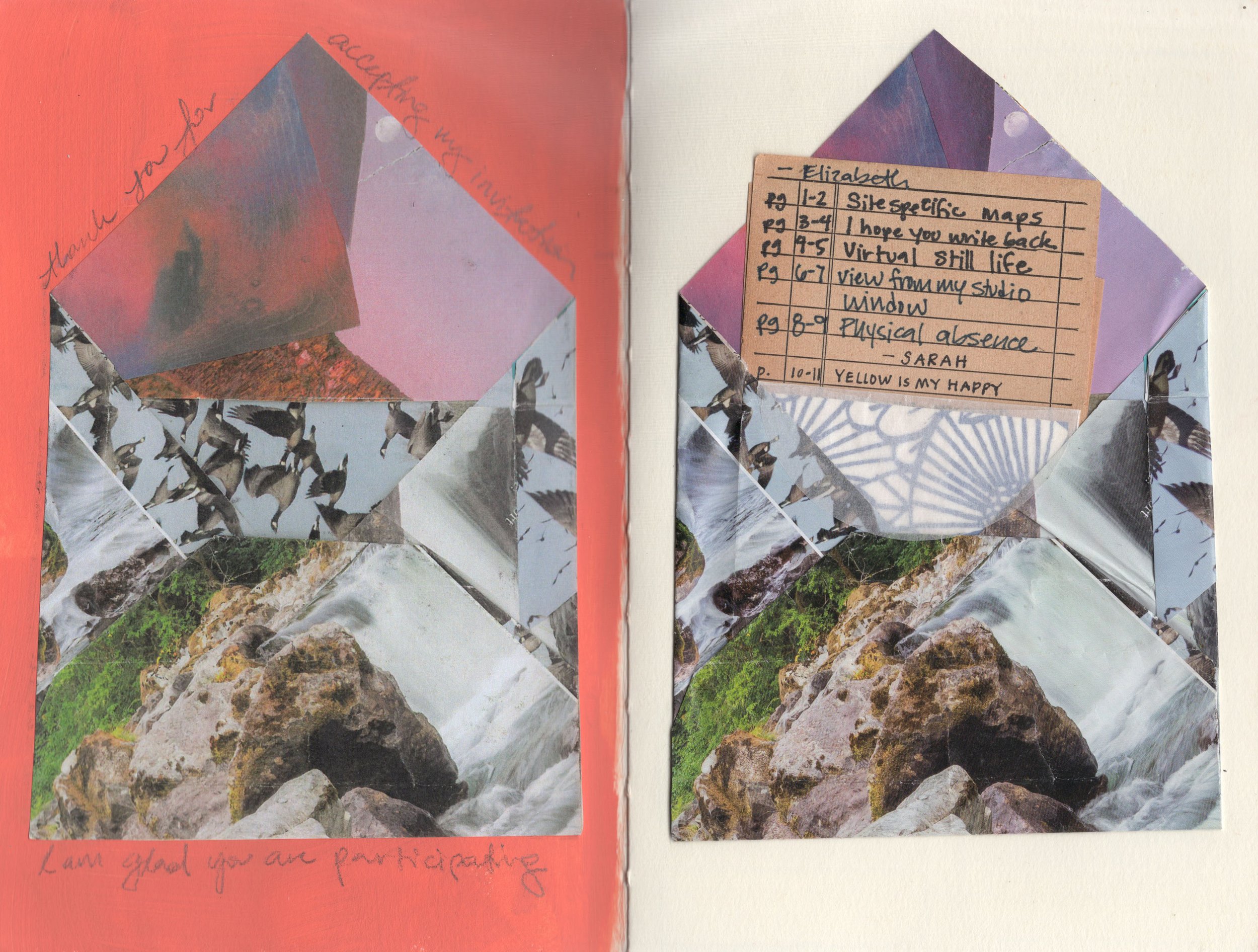

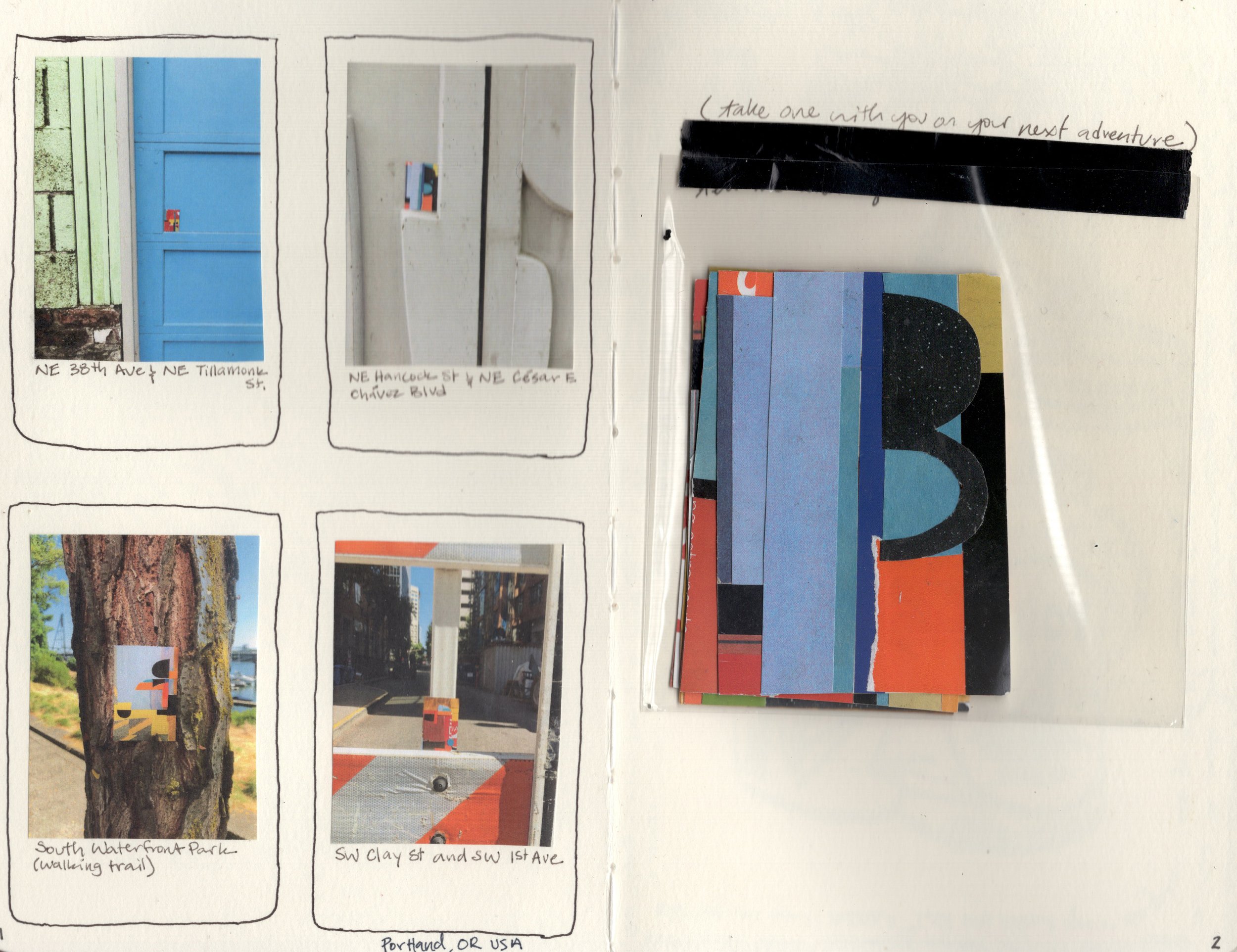

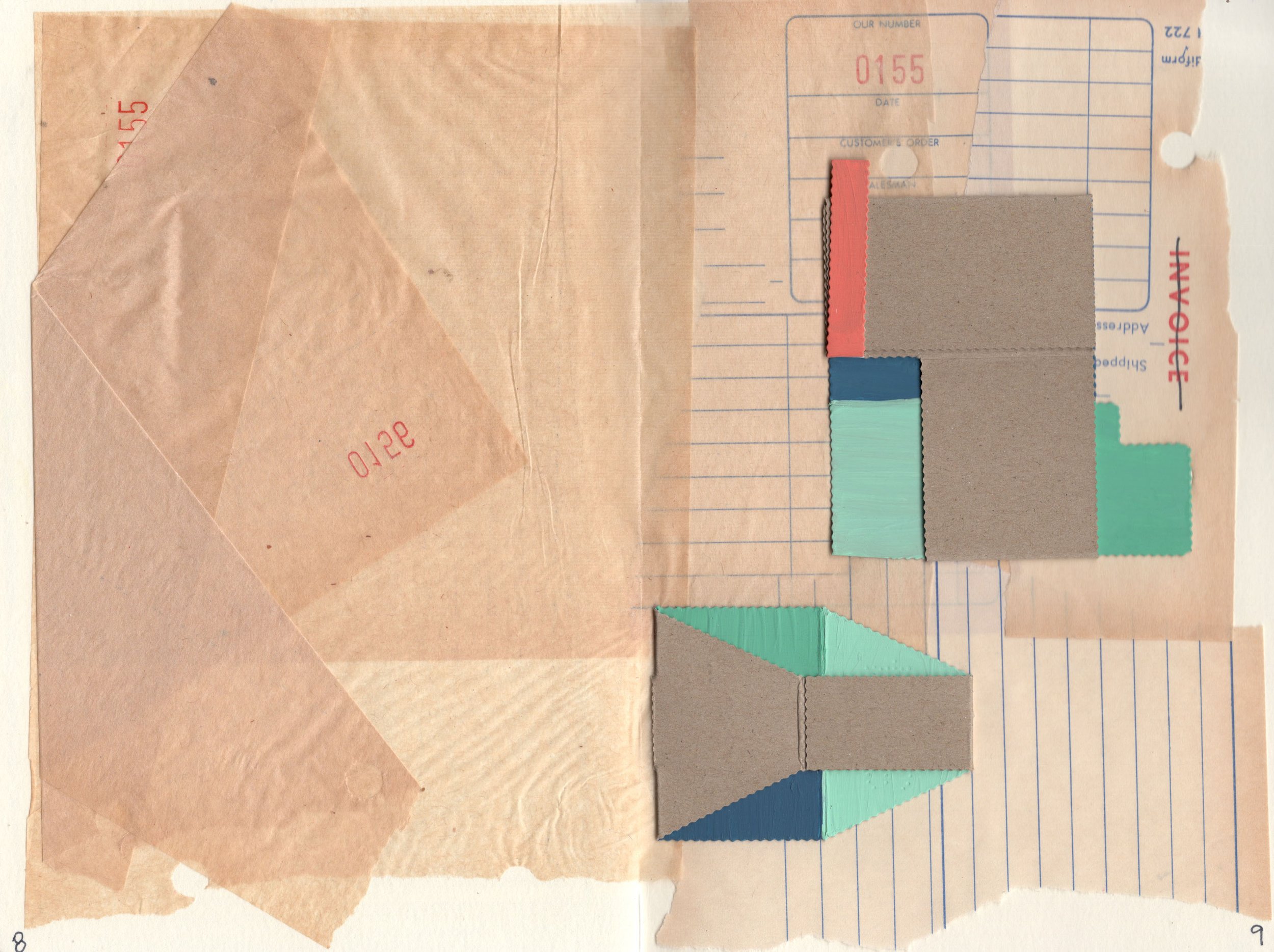

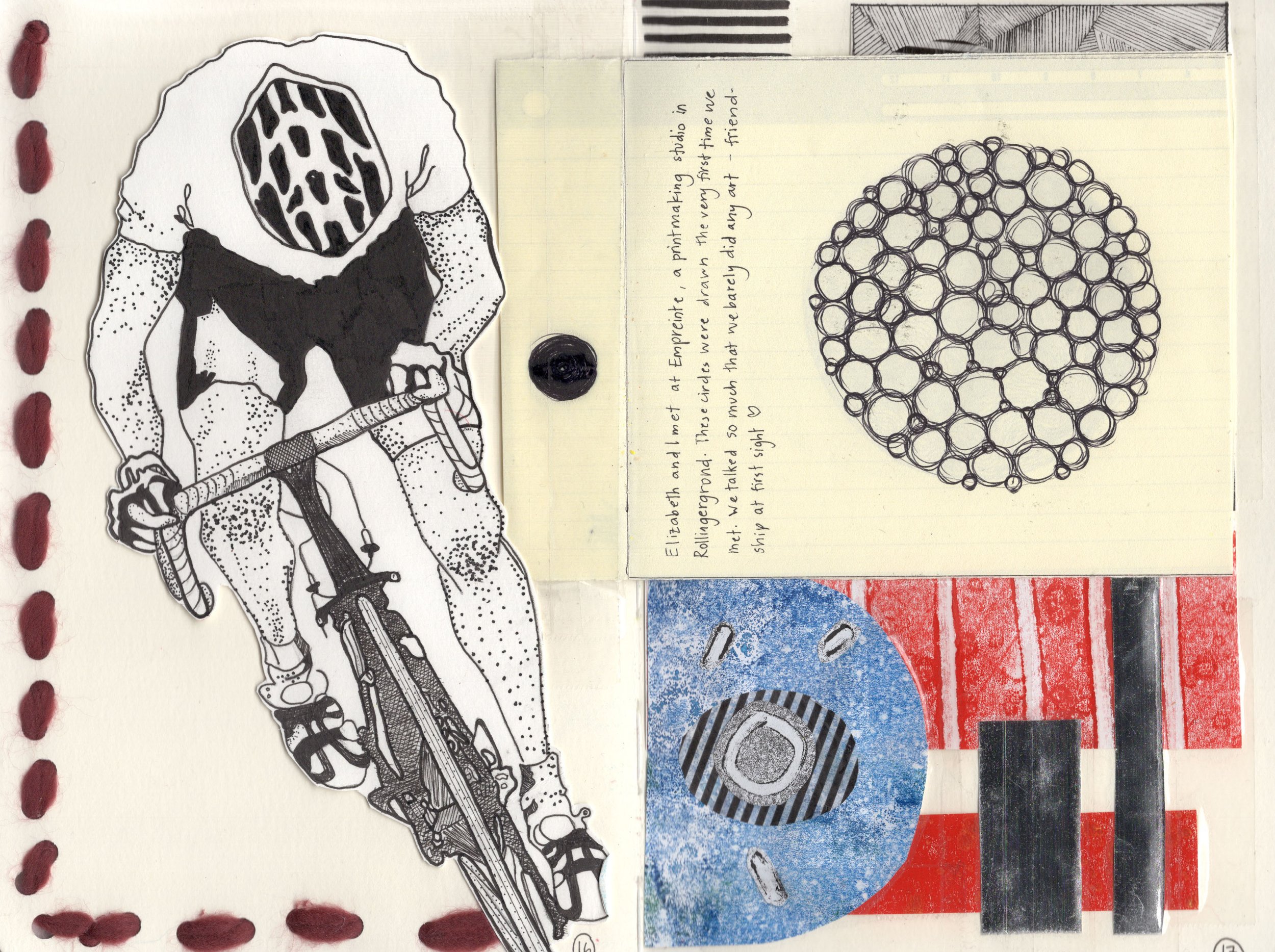

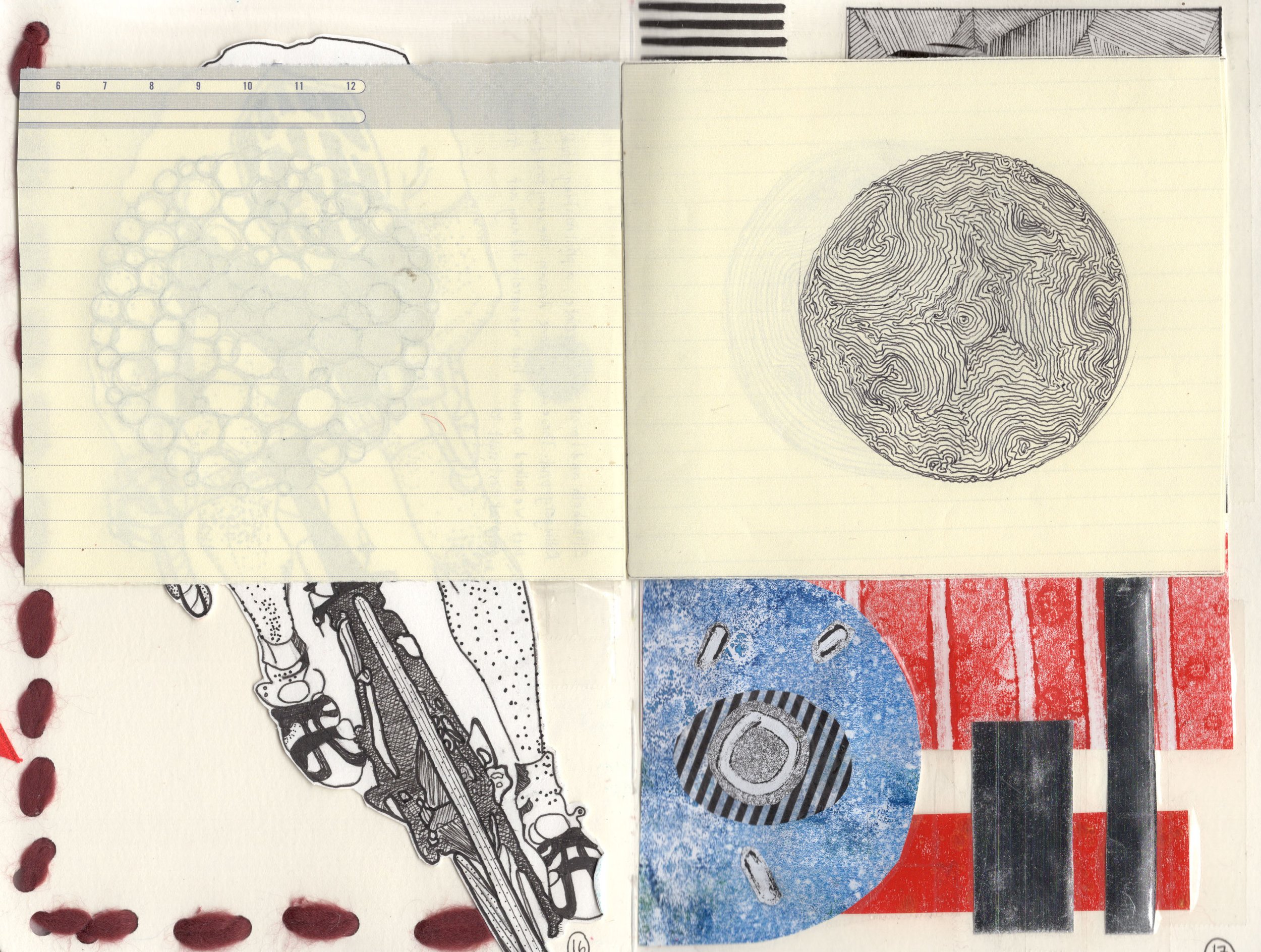

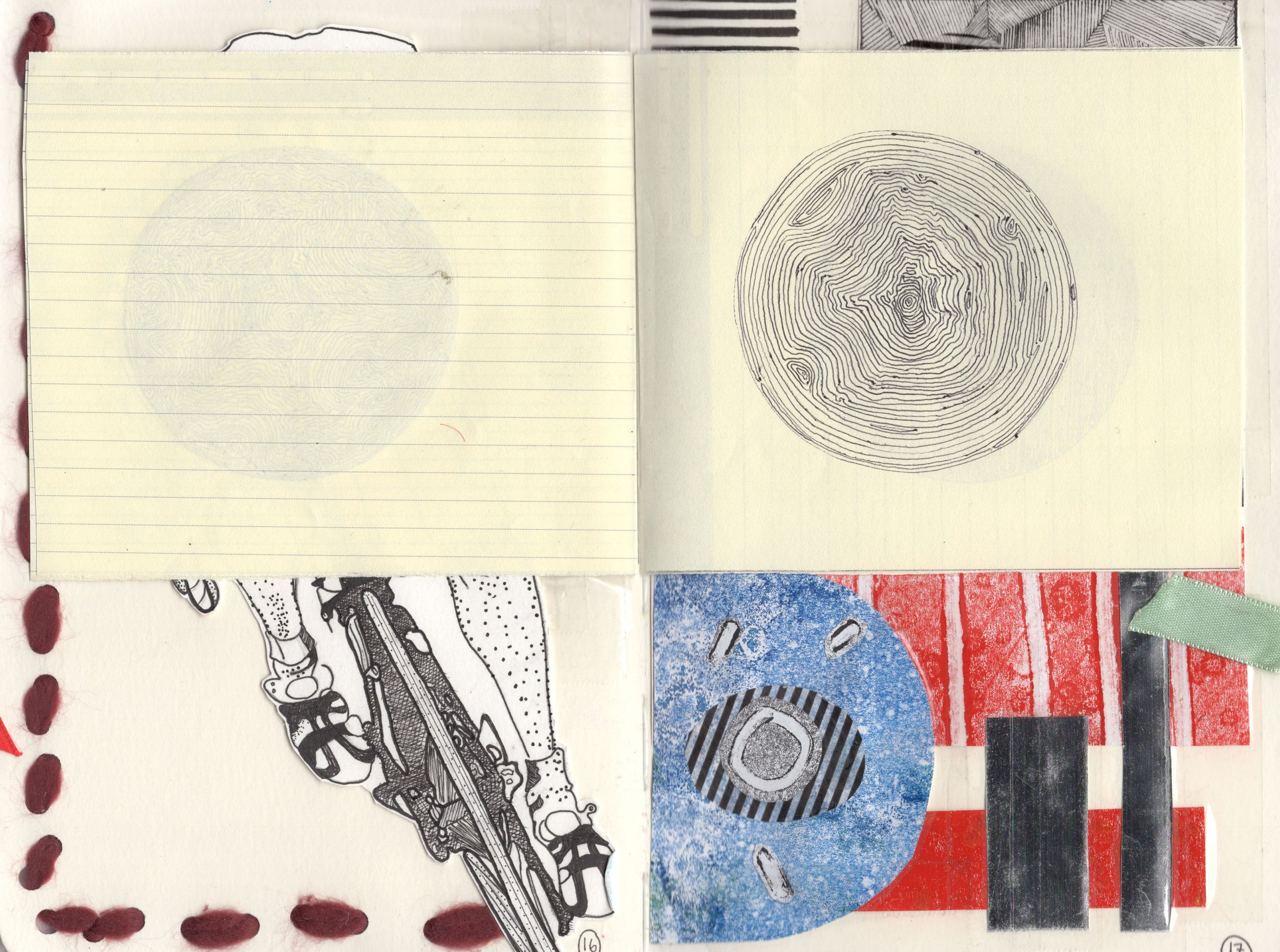

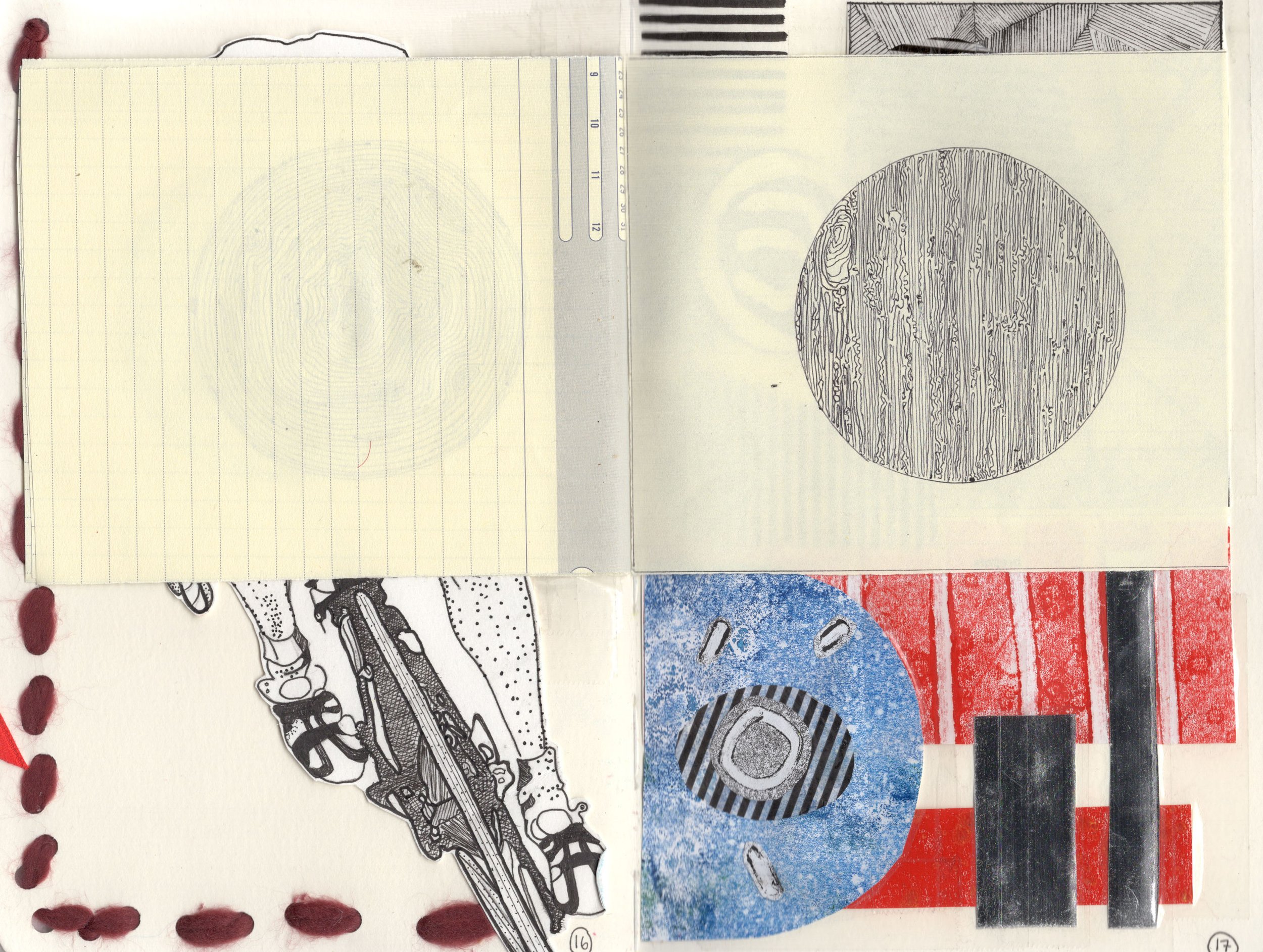

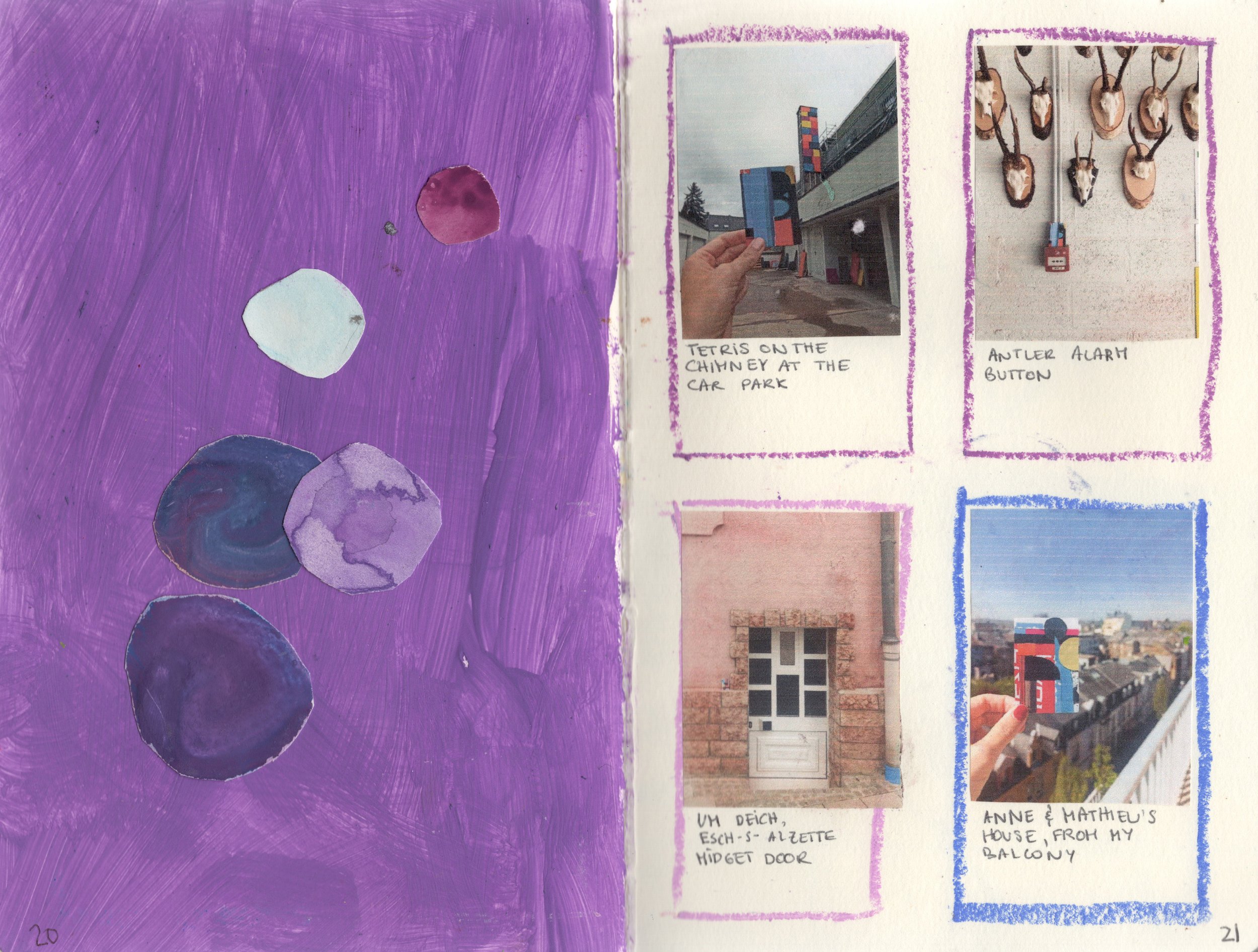

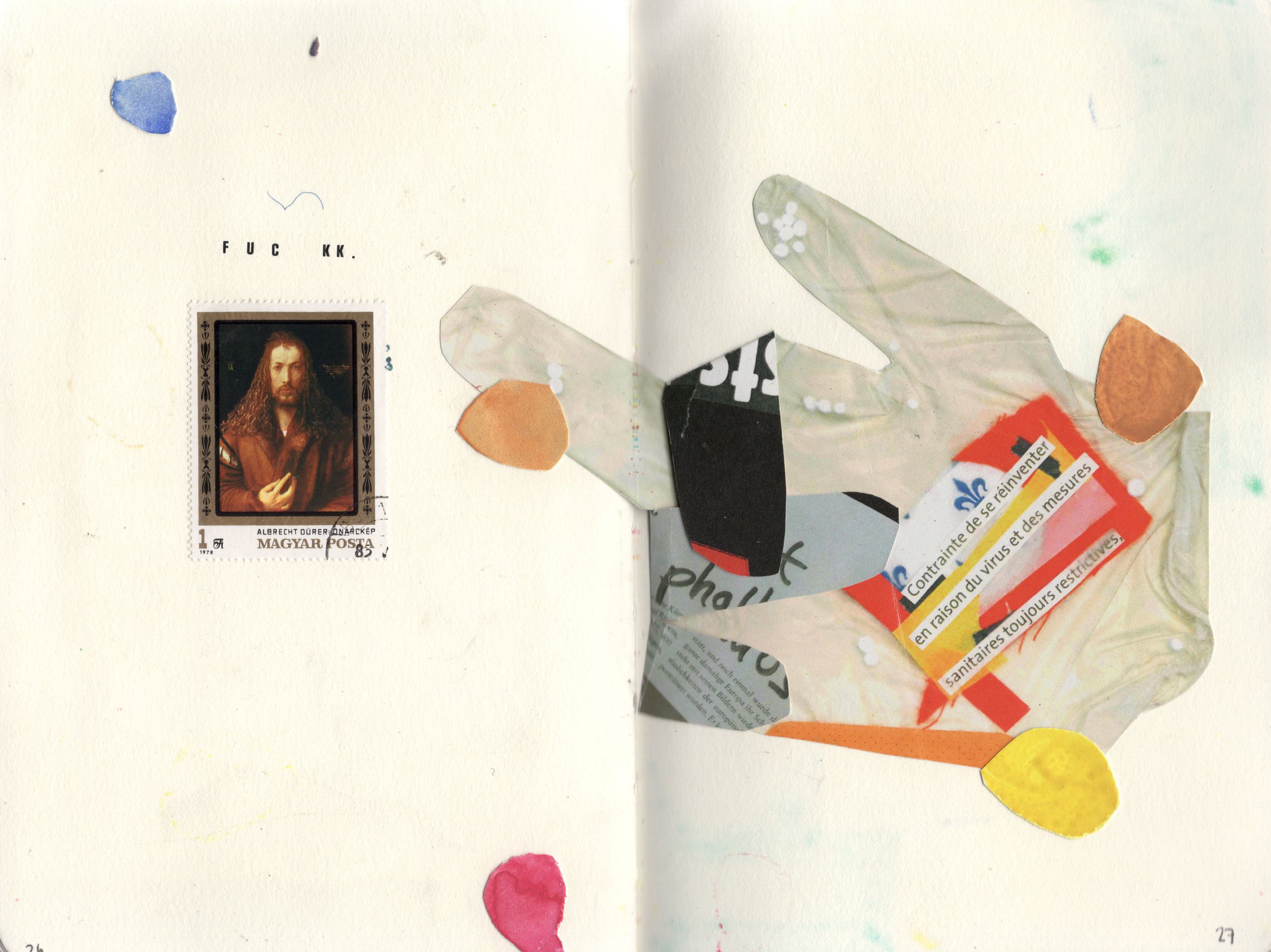

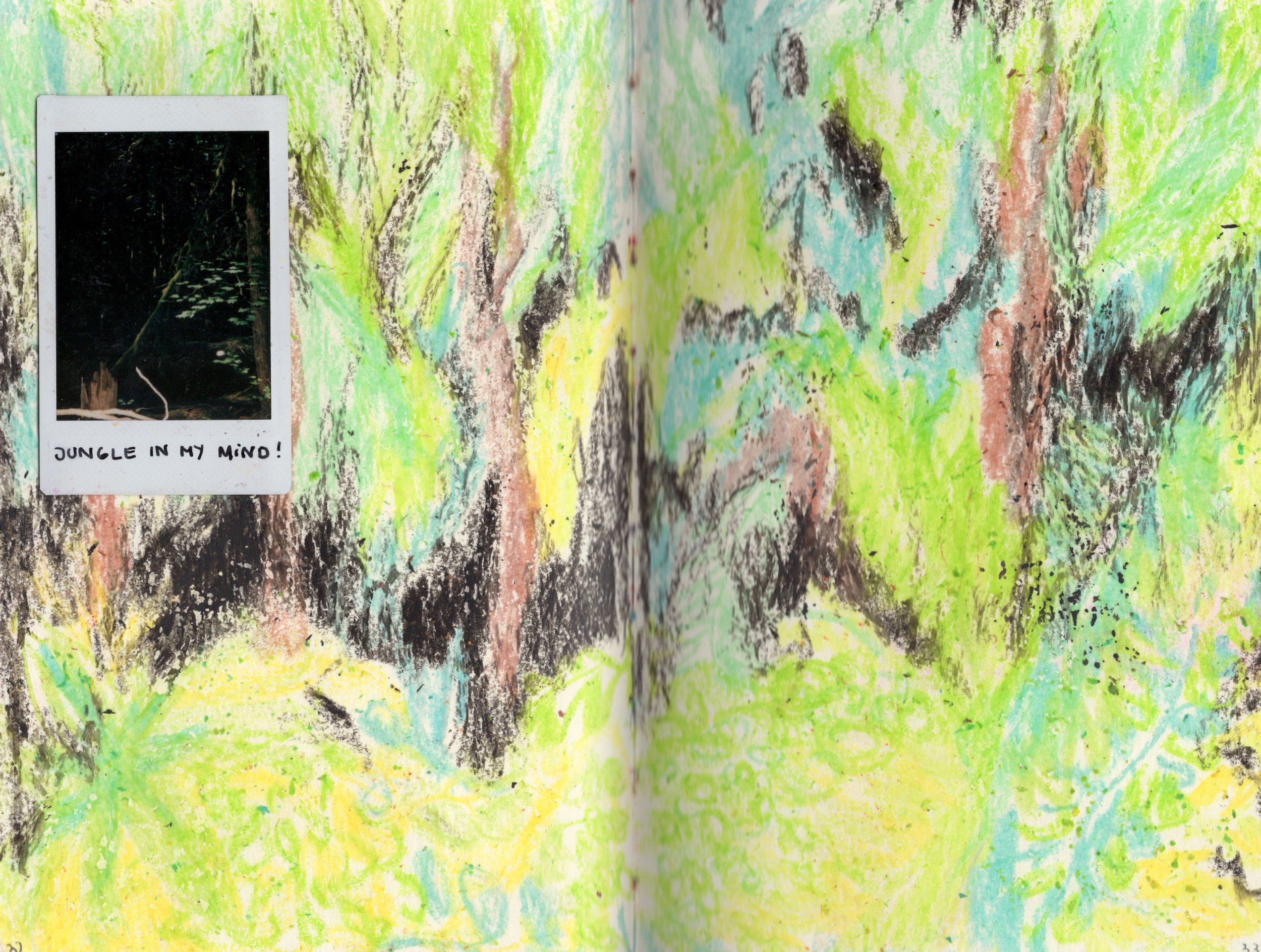

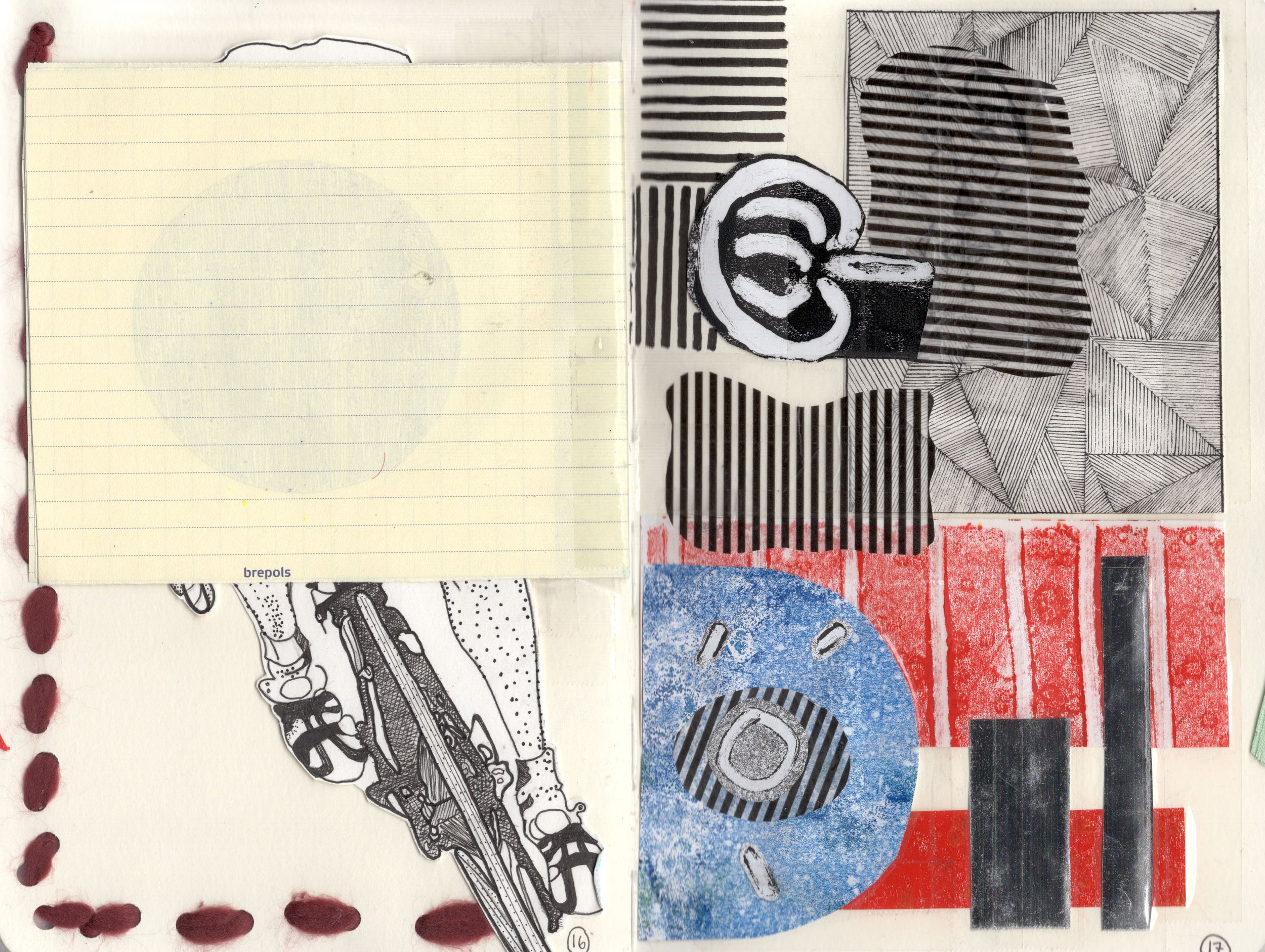

Or most recently in the form of a traveling sketchbook, if we are to think about translation as a process of moving something from one place to another.

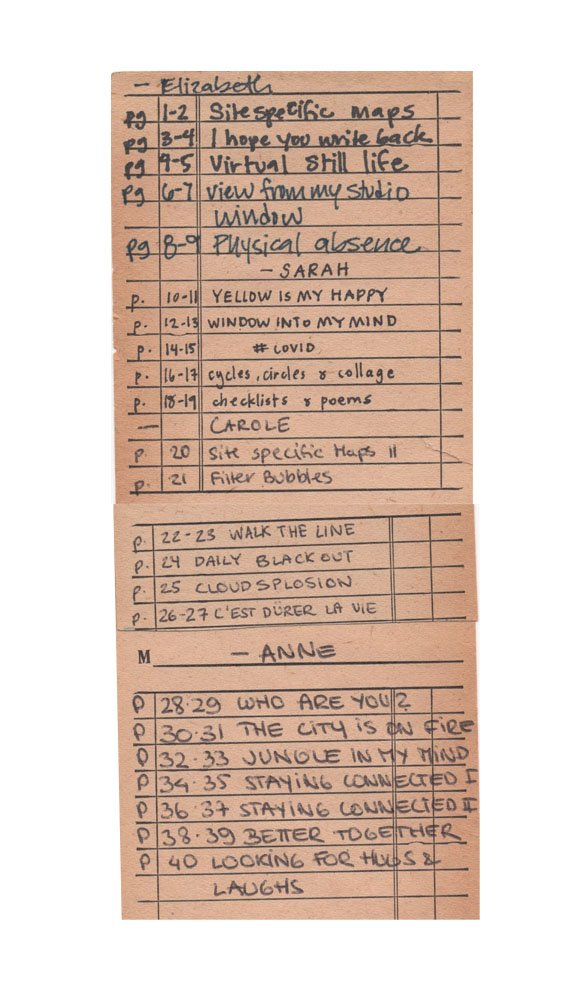

The sketchbook started in Portland, OR with me in August of 2020 and traveled to three other people in Luxembourg before returning to my doorstep this week. Collaborators include: Sarah Ketema, Carole Stoltz and Anne Krier, for which each of their contributions to this project I am so very grateful.

Translation as collaboration: it is the best feeling to send a project out in the world and have it reciprocated by friends.